Few, if any, leading historians voice unqualified objection to the destruction of Confederate monuments. The most tolerant among them instead suggest that the memorials should remain, but with new explanatory inscriptions offering “context”—a code word that simplifies to: South=Bad, North=Good.

Consider, for example, the contextual marker that might be added to Liberty Hall, former home of Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens. No doubt it would emphasize the racist remarks in his Cornerstone Speech. But I’d wager $100 against a good Cuban cigar that it would ignore his address to the Georgia legislature after the war when he urged the body to adopt laws to protect African-Americans “so that they may stand equal before the law” partly because “we owe [them] a debt of gratitude…”

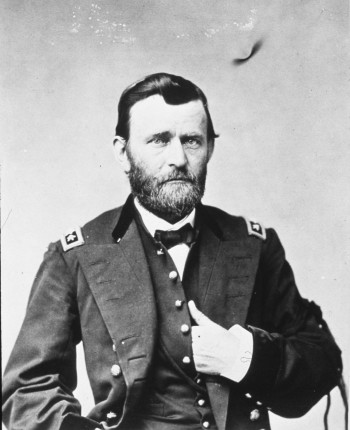

More significantly, adding additional perspective to Rebel memorials begs the question of whether the policy should also apply to Yankee monuments. Consider the Lincoln Memorial. A couple of months before he announced the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862 Lincoln met at the White House with African-American leaders and urged that blacks leave the country. He arranged congressional funding for their emigration.

Addressing his guests Lincoln said: “You and we are of different races. We have existing between us broader differences than exist between almost any other two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this is admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.”

Four years earlier when campaigning to replace Stephen A. Douglas as a U. S. Senator from Illinois, Lincoln explained:

I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races—that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.

Although sometimes labeled the Great Emancipator, Lincoln’s famous proclamation was more controversial than commonly supposed. Contrary to popular belief, many contemporaries were confused, critical, and frightened by its implications. Major General George McClellan, among others, believed it was a deliberate attempt to incite a slave rebellion in the South in order to end the war by forcing Confederate soldiers to return home. Such an interpretation could be inferred from its statement that “the military…authority…will do no act…to repress such persons [slaves]…in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” The British especially feared that the proposal would set an example to ignite genocidal race wars throughout the Western Hemisphere and thereby decimate Atlantic trade.

President Lincoln even admitted the possibility of such insurrections shortly before issuing the September 22nd proclamation. On September 13th he replied to a delegation of Chicago abolitionists visiting Washington that he recognized the potential “consequences of insurrection and massacre at the South” that such a policy might trigger. Whatever the moral benefits, or immoral consequences, of emancipation he “view[ed] the matter as a practical war measure, to be decided upon according to the advantages or disadvantages it may offer to the suppression of the [Confederate] rebellion.”

Consequently, the proclamation led to an uproar about its potential to incite slave rebellions. Ultimately, however, Lincoln inserted a subtle but important difference between the preliminary September ’62 version and the final form issued on January 1, 1863 by adding the following paragraph, which was altogether missing from the September version:

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

It is impossible to know whether the addition represented a change in Lincoln’s policy or merely a clarification of his original intent. But if context must be added to Confederate monuments let’s add it to the historical memorials on each side including our common country’s greatest President, Abraham Lincoln.